The full paper for this research is available here.

Prediction markets are very interesting financial primitives: they are ultimate truth machines, purely driven by incentives.

However - prediction markets have a problem: they always expect binary outcomes.

Turns out, this is very capital inefficient for anything that does not have binary outcomes.

“Will it rain tomorrow?” Sure. Clean binary. A yes or no answer.

But what you actually want to know most days is something like:

- what will the price be?

- how many days until launch?

- what percentage will the vote share land on?

- what will the CPI print be?

In other words: a number. A point on a line.

And the moment you ask a normal prediction market for a number, it kind of panics and starts chopping the number line into little boxes. “Between 40 and 60.” “Above 60.” “Below 40.” You end up buying these disjoint positions like you’re trying to build a continuous belief out of LEGO bricks.

The result is liquidity scattered everywhere and a payoff structure full of cliffs.

The Gaussian Market is a new prediction market protocol that fixes this: traders can bet on any number within a given range, instead of having to choose a binary side.

The whole protocol is a single, unified pool where you just stake on the value you think is right, and then get paid based on how close you were. No “sides.” No long token vs short token. Just a probability surface made out of capital.

Think of the final outcome as a dartboard. The protocol doesn’t ask “did your dart land inside the exact painted square?” It asks “how far from the bullseye were you?” and then pays you on a smooth gradient.

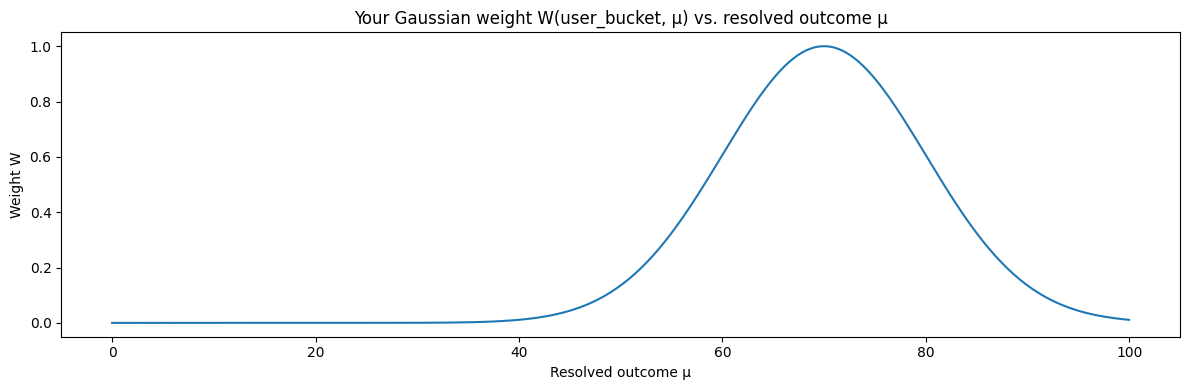

That gradient is:

$$

W(x,\mu)=\exp!\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)

$$

where:

- $x$ is the bucket you chose

- $\mu$ is the realized value

- $\sigma$ is the “how forgiving are we today?” knob (the width of the bell curve)

If you hit dead center, $x=\mu$, then the exponent is $0$, and you get maximum weight:

$$

W(\mu,\mu)=1

$$

If you’re off by a bit, you still get a real score. If you’re off by a lot, your score fades out smoothly toward $0$.

Gaussian Markets are parimutuel: one pool in, one pool out. The protocol just redistributes it.

Users stake into discrete buckets:

$$

k \in {0,1,2,\dots,N}

$$

Let $S_k$ be the total stake sitting in bucket $k$. Then the total pool is:

$$

P_{\text{total}}=\sum_{k=0}^{N} S_k

$$

Now the protocol needs one more ingredient: a way to normalize payouts so the whole thing is self-contained and always sums correctly.

That’s what $Z$ is.

$$

Z=\sum_{k=0}^{N} S_k \cdot W(k,\mu)

$$

$Z$ is: “how much of the pool was close to the truth, once we score closeness with the bell curve.”

And then the entire payout rule is almost offensively simple.

If you stake $s$ on bucket $x$, your payout is:

$$

\text{Payout} = P_{\text{total}}

\cdot

\frac{s \cdot W(x,\mu)}{Z}

$$

That’s it.

The protocol is basically saying:

“We’re going to split the pot in proportion to accuracy-weighted stake.”

So if you were closer than the crowd, you get a bigger slice.

If you were further, you get diluted.

If you were near correct, you still get something (which is kind of the entire moral argument of this design).

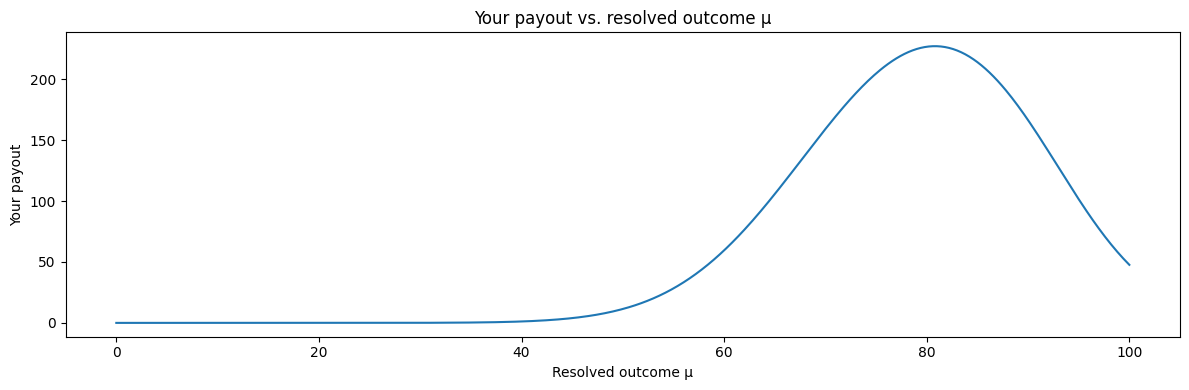

A tiny example:

Suppose we run a market from $0$ to $100$.

- Total pool: $P_{\text{total}} = 200$

- User A stakes $100$ at $x_A=10$

- User B stakes $100$ at $x_B=70$

- Outcome resolves at $\mu=50$

- Set $\sigma=15$

User B is closer (distance $20$) than User A (distance $40$), so their bell-curve score is way higher.

When you run the payout rule, User A doesn’t get vaporized into $0$ – they get a partial recovery – and User B takes most of the pot.

How it actually feels to trade

The easiest way to understand Gaussian Markets is to stop thinking “I’m betting on a box” and start thinking “I’m painting a belief curve.”

If you think the answer is around $52$, you stake near $52$.

If you think it’s around $52$ but you’re not totally sure, you can spread your stake across a small neighborhood:

$$

x \in [48,56]

$$

You are expressing uncertainty by widening your footprint.

And the protocol grades you using the same kind of thing you’d use to grade a guess in real life: “close enough counts.”

“Continuous markets” that are actually continuous on-chain

Under the Gaussian Markets model, the market as a “probability surface” where stakes behave like a collective density.

That’s a fancy way of saying:

Instead of splitting liquidity into 20 awkward markets, you get one deep pool where the shape of capital tells you what people believe.

One design detail: the protocol never has to do anything expensive like “iterate over users.”

Instead, it iterates over buckets (a fixed small set), computes the denominator $Z$, and stores weights.

Then users claim their payout later (“lazy claim”), using the already-stored weights and $Z$.

Mechanically, that’s how you get something that feels like a continuous prediction market without turning the EVM into a bonfire.

The punchline

Gaussian Markets take the thing people actually want – a market over a continuous variable – and stop forcing it through the binary blender.

They keep the most important idea dead simple:

- You bet on a value $x$

- The truth shows up as $\mu$

- You get scored by distance with a bell curve:

$$

W(x,\mu)=\exp!\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)

$$

- And you get paid your share of the pool:

$$

\text{Payout} = P_{\text{total}}

\cdot

\frac{s \cdot W(x,\mu)}{\sum_{k=0}^{N} S_k W(k,\mu)}

$$

If you’ve ever felt like prediction markets should pay you for being “less wrong,” instead of only rewarding perfect category hits, this protocol is basically that instinct turned into math; and then turned into a mechanism you can actually run. ■